Guernsey cattle, fresh seafood team to create memorable Channel Islands cuisine

A family picnics while overlooking Lihou Island, a wildlife reserve with ruins of a 12th-century priory. It’s reachable on foot from Guernsey at low tide.

The English Channel Islands are bathed by the Gulf Stream with a frost-free climate that results in the ability to grow lots of things rarely seen in other temperate parts of the world.

Thirty-foot tides twice a day expose, then hide, the white sand beaches, and rich undersea resources delight fishermen. Oysters, lobsters, mussels and fish are harvested from the sea every day and rushed into restaurant kitchens to appear on tables within hours.

During my visit to Guernsey and Sark in June, I at first thought these were the main reasons for its restaurants’ devotion to good eating. I was blown away by the abundance, variety and expertise shown in the preparation and treatment of food.

But the near-starvation of the populace during the World War II Occupation Years is, perhaps, a legacy responsible in part for the excellence of dining on Guernsey and Sark. Folks there have a greater appreciation for meals.

When the Nazis occupied the English Channel Islands for six years during World War II, they shut down fishing to limit escapes by boat; took over homes, evicting long-time owners; and rationed everything from salt and flour to sugar and milk. Meat was rare and often came only by slaughtering the island’s Guernsey dairy cows.

Guernsey cattle, known for their rich golden milk and cream, graze in a meadow on the island of Guernsey.

Islanders became creative in making do and living off the land. They made tea from brambles in the hedgerows, harvested seaweed called carrageen moss to replace gelatin, cooked vegetables in seawater and processed beets for sweetener. Those who could grow corn learned to mill it into flour, and some farmers began to grow tobacco to use for barter with the Germans, who also were starving near the war’s end.

The arrival of Red Cross ships and the delivery of food packages to families saved hundreds from death by starvation near the end of the war. On May 9, 1945, British forces liberated the Channel Islands, and the occupying forces surrendered peacefully. That date continues to be celebrated every year.

Guernsey and its occupation in World War II were the backdrop for the recent blockbuster novel and subsequent film “The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society.” Although the story is a fictional account based on facts, visitors today can walk in the footsteps of those invented characters as they explore the island’s military defense sites and discover a little about everyday life under German rule.

My first meal on Guernsey was far from the potato peels that were a mainstay in that earlier time. Our small group was escorted to a table at Octopus, a fine dining restaurant 20 minutes from the airport at water’s edge near the main town of St. Peter Port.

There, I was served a seafood pot with a whole crab surrounded with little octopi, mussels, scallops and potato chunks dressed in a cream sauce crafted from Noilly Prat extra dry vermouth. The French coast of Normandy is just a few miles away, and I was not surprised to discover Octopus is operated by a pair of French expats who also own another restaurant in Town, as St. Peter Port is known by the locals.

The restaurant Octopus serves a crab surrounded by octopus, scallops and other seafood napped in a vermouth sauce made from rich Guernsey cream.

It was the rich cream sauce in the meal that caught my attention — my introduction to Guernsey dairy products.

It was just the first of many meals celebrating the island’s unique location in a deep gulf off the coast of France.

Guernsey was, at one time, a part of Normandy following the 1066 victory in the Battle of Hastings by the Norman Duke William II, best known as William the Conqueror. Two centuries later, King John lost Normandy to France, and the Channel Islands were given the choice of remaining loyal to the English Crown or reverting to France. When they chose loyalty to England, they were granted the continuance of their ancient laws that form the basis of today’s government.

Fear of being captured by France led to the construction of Martello towers along the coasts in the 1700s. Many still can be seen today.

Of course, I’d heard of the famous Guernsey cattle, a brown-and-white breed known for producing very nutritional milk. Historians believe the breed was created long ago by a group of monks sent to Guernsey by Robert I, Duke of Normandy to educate the islanders. They brought the best bloodlines of French cattle to create the Guernsey breed. The first Guernsey cattle were imported to Britain in 1724, and soon they were being taken around the world.

The distinctive golden milk the cows produce quickly caught the world’s attention. Scientific analysis reveals that Guernsey milk contains three times as much beneficial omega-3 fatty acids than other milk, 30 percent more cream and 33 percent more vitamin D. The World Guernsey Cattle Federation said the milk’s golden color comes from its high content of beta carotene.

Guernsey hotelier Luke Wheedon, who hosted us for dinner and a gin tasting at his Bella Luce Hotel, claims that sauces using Guernsey milk become thicker and richer, while pastries made with its butter get a creamier taste.

“When baking and frying, meats take on more color, and fatty fish like plaice and sole get a delicious buttery taste,” he said. “The elastic structure of Guernsey butter works amazingly well with ingredients and causes it to melt sooner than other butters.”

Another, more formal, Taste of Guernsey dinner was enjoyed at The Old Government House, our elegant accommodation during our days on the island. South African wines were poured, reflecting the heritage of the hotel’s Tollman family owners. The Tollmans’ Red Carnation Hotel Group includes 17 hotels in the U.K., Ireland and South Africa, along with two in Guernsey. The company also has the Bouchard Finlayson Winery in South Africa. Those wines are served in all their hotels.

Breakfasts, included for guests at that five-star hotel, consisted of unusual and tasty butternut squash pancakes; smoked haddock; oak smoked kippers; and kedgeree, a traditional British breakfast dish of rice, fish and eggs that has its ancestry in India.

The Old Government House once was the mansion home of the island’s governor.

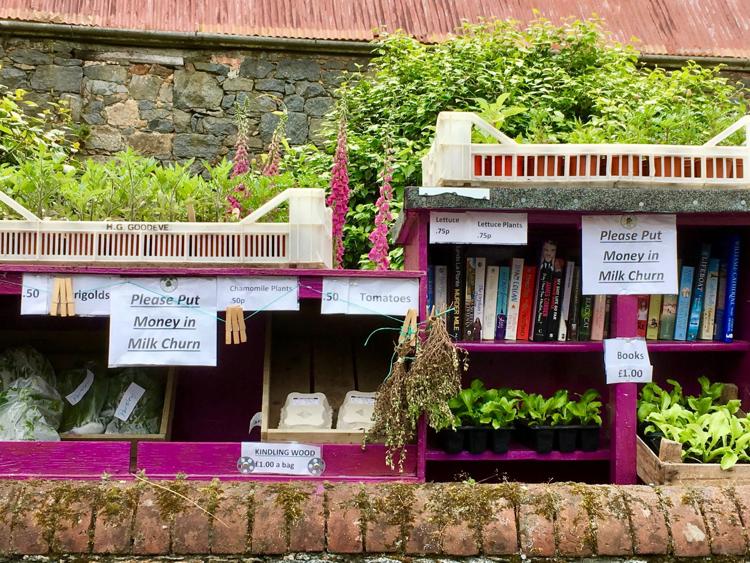

I quickly discovered tastes of the world are part of life on Guernsey, despite its diminutive 25-square-mile size and 60,000-person population. It’s clearly a very sophisticated constituency with sweet down-home customs such as the Hedge Veg — roadside stands cut into the stone and greenery hedges that mark properties. Residents put out things they’ve harvested along with firewood, books and other things requesting passersby to put their payment in a milk churn.

Hedge Veg is what islanders call the roadside stands carved into hedgerows and operated on the honor system by Guernsey residents.

Samphire, a European parsley relative that grows on Guernsey’s rocks and cliff, made its appearance in several meals.

When I puzzled over the fish names on the menu at Le Nautique, Chef Gunter Botzenhardt offered to prepare several of them and serve them together so I could taste the difference. That day I learned the side-by-side tastes of turbot, monkfish and brill, and Le Nautique was elevated to a dining favorite.

Guernsey oysters often make an appearance at meals, and they’re also pretty amazing. They’re grown in the nutrient-rich waters of Herm, fed by the tidal flow of the Gulf Stream and take on the flavor of the water that nourishes them. Because Guernsey oysters aren’t afflicted with a widespread oyster disease, Guernsey Sea Farms supplies clean oyster seed to farms around the world.

Oysters raised in the nutrient-rich waters of Guernsey and Herm are served throughout the Channel Islands and are in demand all over the world.

Apples grow well on Guernsey and have been crushed into cider for centuries. At Rocquette Cidery, there’s a circular stone trough dating to the 16th century, used back then for crushing apples. A half ton of apples could be crushed in a day to make 100 gallons of apple juice for fermenting into cider. Today the crusher is preserved surrounded by flowers to tell about cider’s history on Guernsey. We’re served various cider tastes accompanied by wonderful Guernsey cheese — a match made in heaven.

We travel to the west of Guernsey to see the offshore island of Lihou, a population picnic destination and windswept nature reserve, which can be reached on foot at low tides. Ruins of a 12th-century priory, built by Bendictine monks atop the ruins of three megalithic dolmen and seven menhirs, was used for target practice by the Germans during World War II. A sign near the stone causeway advises of the high tides that can strand those who cross at the wrong times.

Nearby is La Creuax es Faies, another megalithic tomb believed built around 3000 B.C. Legend says that fairies come out to dance on the headland on moonlit nights.

On this enchanted island I can believe it.

Recent Comments